Taking good notes in class or from your textbooks is arguably one of the most significant components of your studies. After all, it is where you store all the information that you need to learn for your exams, yet it does not naturally fall into a straightforward and streamlined process. With a new academic year beginning and a whole new load of courses to undertake, this is the time to start building good note-taking methods to start your year right.

Whether it be to simply bump your grade up a little or because you finally decided that this year, you will become an academic weapon, there is one thing you should know to avoid at all costs to begin with.

Don’t transcribe

Have you ever taken notes with a computer before? I remember using Notion on my laptop back in my junior years for online courses where I did not bother buying a physical textbook to write in. As a guy who types at 130WPM, it was relatively easy for me to take down every single thing that the lecturer was saying. But what I ultimately ended up with was huge walls of text with too much information, some of which, I couldn’t even understand because I was too occupied with typing rather than understanding.

While writing by hand is certainly not fast enough to note down everything a teacher has to say, I have still seen many students transcribe notes over my time at Macleans, many of whom have a knack for writing down everything a textbook or slideshow says. While on paper instead of an app, this still achieves the same result, which is a big wall of writing. Though you may have the fear of missing something important a teacher says or puts onto a slideshow, there is simply no point in writing down everything that is said. Quite frankly, it is an inefficient use of time as you spend too much time taking notes and then spend even more time revising as you have to wrap your head around your transcription while summarising it into bite-sized information for your brain to encode.

What you should be focusing on instead is how to condense information into short, important points and how to categorise information so that you can chunk details together. Don’t be scared to also incorporate abbreviations of words (such as changing different to diff.) to make your notes more succinct. With the big “what NOT to do” out of the way, let’s dive into how exactly you can approach these goals with your note-taking.

Outline Method

This is the default for most students when they note-take and it is also my personal favourite! This is as straightforward as it gets, involving a simple three-step process:

- Start with a main point for your topic

- Nest any sub-ideas below the main point with an indent or a different symbol,

- Nest any further details for the sub-ideas with another indent or different symbol

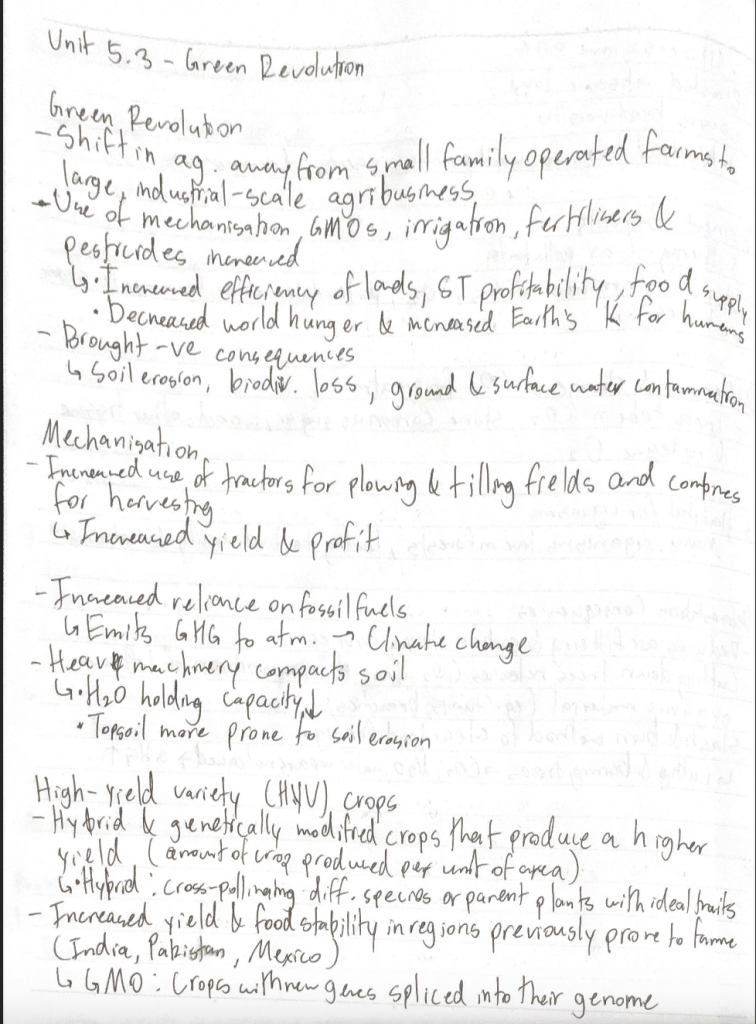

Here is an example from my own notes I took for environmental science.

The outline method serves as an incredibly easy way to create organised notes due to its easy-to-follow methodology. If you are looking to create better notes, this is where I would suggest you start. However, as easy as this method is to use, it can just as easily be misused if students add too much detail to their main points, essentially resulting in transcribing.

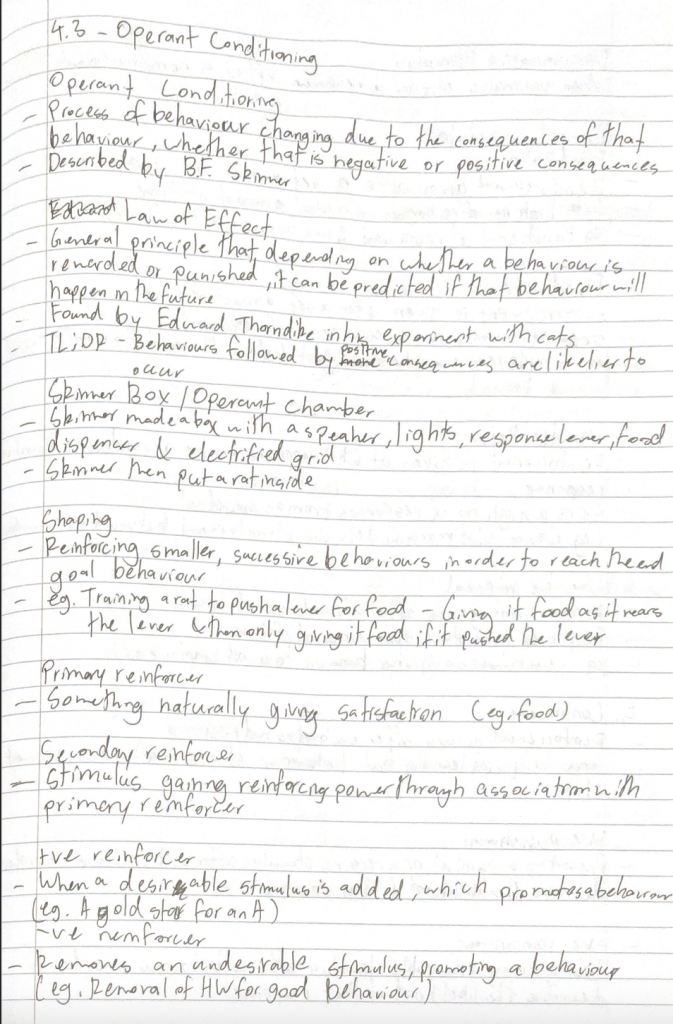

Cornell Notes

As suggested by the name, this method comes from Cornell University, more specifically, education professor, Doctor Walter Pauk who advocated for a “two-column” style of note-taking for college and university students. Cornell Notes involve splitting a typical page up into two columns with a 1:2 ratio, one for cues (main ideas, questions connecting points, diagrams etc.) on the left-hand side) and the other for actual note-taking on the right-hand side. A little space about the size of a paragraph is left at the bottom of the page where you can write the summary of the notes.

This method is essentially a more elaborate version of your typical outlining method with its extra components. Cornell notes carry the same benefits of the outlining method as it forces you to condense information and therefore, be more concise while taking notes but also provides additional pros. The cues section allows you to capture any questions that you may have in mind so that you do not forget them later on and can be great for providing additional information for your topic through means like diagrams or notes on the types of exam questions asked surrounding your main topic. Meanwhile, the summary section forces you to note down the big picture of whatever topic you’re learning, allowing you to have a general overview of what you studied when looking back on your notes before diving into the details.

While well-intentioned, Cornell notes do come with their flaws too, though quite minor overall. The elephant in the room is that note-taking space is quite limited, which is especially a problem since students are expected to take notes using physical books at Macleans. For those who would prefer to have topics limited to one page, this could lead to some formatting issues. Another problem is the summary itself; although it is useful for synthesising information, it isn’t really useful for fact-based learning and is more suited for concept-based learning. Could you imagine having to cram all these facts into a summary paragraph? It would be mayhem.

This is why I would typically opt for a modified Cornell system when tackling fact-based subjects with only the cue section and the notes section or simply default back to the outlining method.

Mind Mapping

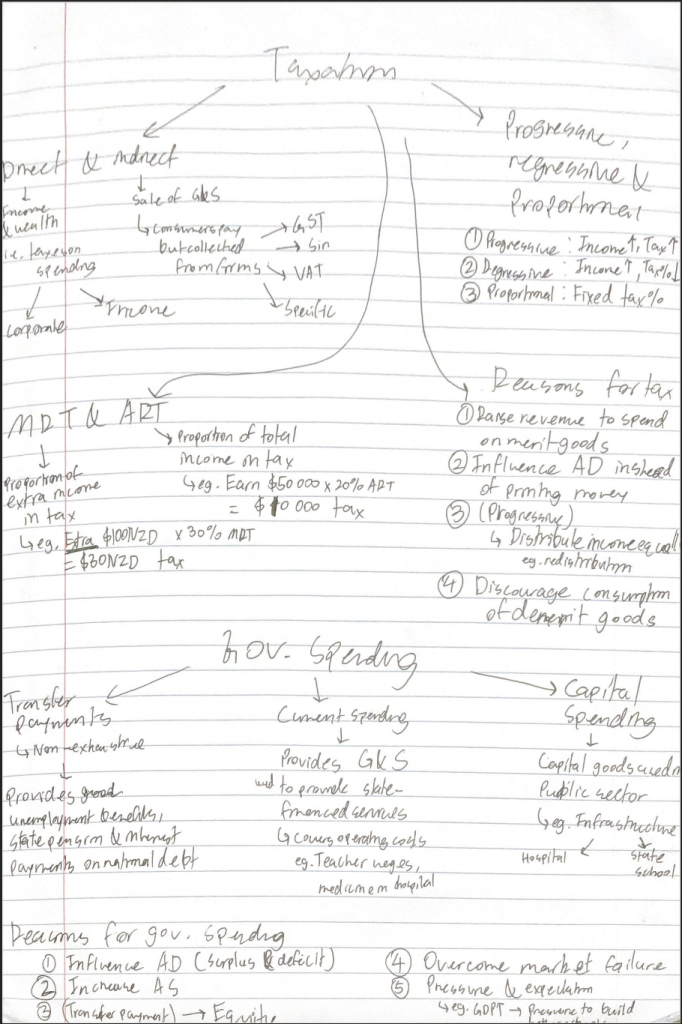

Lastly, we have mind mapping, a method that some of the smartest people like Elon Musk swear by. Though being an amazing system to utilise, especially for revision and SWOT notes, it is the most difficult method out of the three to execute well.

Compared to your standard notes, mind mapping is superior in terms of expressiveness, taking advantage of visuals, analogies and associations, making it far more efficient for review than having to read through a plethora of writing. Furthermore, the expressiveness of mind mapping allows you to understand how all the key details of a particular topic ultimately lead back to the big picture.

To execute a mind map effectively, there are a few steps that you must carefully follow:

- Have an overarching idea (eg. Price stability)

- Branch out the definition of the key idea and then all of its key concepts (eg. Inflation, deflation, disinflation, causes of inflation, types of inflation)

- Branch out key details of each concept, focusing on chunking them, looking at categories like how they relate, compare or contrast, or if they are cause and effect (eg. Factors that cause cost-push inflation)

- Be expressive with ideas in visual form or analogies (eg. Instead of writing out the definition of cost-push inflation, draw out the diagram that expresses it visually)

As effective as mind mapping is for capturing important information and synthesising it in a digestible manner, the nature of its difficulty in execution is the biggest weakness of this method. It is easy for students to make mistakes along the way such as getting too lost in the details, using too many words, or not taking advantage of visual representations and many more. My advice to mitigate this is to simply mind map more and constantly review older versions that you have made, looking at what had been done well and what went wrong.

Let’s take a look at one of my SWOT notes on fiscal policy for economics.

Now that you’re equipped with the tools required for success in one of the major areas of academics, it’s time to start implementing it. Don’t wait, start practising these methods immediately perhaps with videos or past slideshows posted by your teacher and then begin implementing it into your actual note-taking in class. Of course, it may not be perfect the first time you use these methods; I know that was certainly the case for me. But through a series of trial and error as well as learning from your mistakes, these methods can propel you to academic success as you improve how you capture information and review it.

Good luck readers, with your 2024.

8th February, 2024

Written by Aaron Huang, edited by Amelia Hu